Book Review - Archaeopteryx: The Icon of Evolution

On a recent trip to the Houston Museum of Natural Science, I bought a ticket to see the the exhibit, Archaeopteryx: Icon of Evolution (related link). The exhibit was a fascinating collection of fossils from the Solnhofen region of Germany, with an archaeopteryx known as the Thermopolis specimen as the centerpiece. The archaeopteryx fossil was very interesting, but there were two things about it, in particular, that I was struck by. First was the size. For some reason, in my mind's eye, archaeopteryx had always been a big bird, something along the lines of an eagle. The archaeopteryx fossil at the museum was about the size of a crow (more on this below). Second was the level of detail in the feather imprints, which photos just don't do justice to. It's not that the feathers were imprinted perfectly in their entirety, but in the regions where the preservation was best, it was very obvious that you were looking at an actual feather.

The Thermopolis Archaeopteryx, With a Hand for Comparison to Show Size

So, after I left the exhibit, I went to the museum gift shop to find a souvenir. About the only thing they had that was appropriate for an adult was the book, Archaeopteryx: The Icon of Evolution, by Peter Wellnhofer*.

Before I get started with my own review, let me note that the publisher has a great section for the book. Perhaps best for someone considering buying the book is the section of sample pages. The pages shown are not anomalous - nearly every page had many illustrations, which was great. Also note the small text size and amount of text per page. Even though the book was only 208 pages, it was an information packed 208 pages.

The book was divided into several sections. The first was a short description of the locale where the fossils were found, the Solnhofen region of Bavaria, in Germany. It was the sort of description you'd expect from a chamber of commerce.

Next came a brief description of the geology of the Solnhofen region, and what this tells us about the ancient environment of the area. All of the archaeopteryx specimens found so far have come from Solnhofen Jurassic limestone deposits. It turns out that these deposits were from lagoons in shallow seas. The water was apparently fairly calm, and formed stratified regions with very low oxygen levels at the sea floor - no multicellular life could survive in those anoxic conditions. The mainland was not very close, but it's possible there were islands nearby. So, the limestone deposits were necessarily not the native habitats of any of the terrestrial animals found there. It's possible that the archaeopteryx were blown out to sea during storms, and didn't have the strength to fly back to land (the fact that all archaeopteryx found thus far are juveniles supports this idea).

Death March of a Horseshoe Crab, Which Died after Wandering into an Anoxic Lagoon

After that came a discussion of the history of fossil discovery in the Solnhofen. Obviously, being a marine environment, most of the fossils from the region are from sea creatures, with the fossils of terrestrial animals being very rare. Because of the way the fossils were formed, the preservation is excellent, and Solnhofen fossils have been prized for centuries. They were regular inclusions in the curiosity cabinets of medieval Europe, which emerged in the 16th century (some of the best collections served as the start of modern museums).

Next came the heart of the book - 83 pages discussing the known archaeopteryx specimens in detail. If you think 83 pages of discussion sounds like a lot - it was, and it was a bit dry. I think of myself as a fairly knowledgeable layperson when it comes to evolution and biology, but much this section was a bit advanced for me. The fossils were described in technical terms (radius, ulna, meta carpal, flexor tubercle, pneumatic foramina), which would have made a firm grounding in anatomy useful in understanding this chapter.

This section started with a discussion of how the urvogels (a common name for archaeopteryx from German, meaning proto bird) likely became fossils - they floated in the sea for a few days before sinking to the sea floor, where they were covered with a microbial film before being covered by sediment. One fact I found interesting is that the feathers formed an imprint in the sediment before decomposing, and then this imprint was transferred to the adjacent layer of sediment after the feather decomposed. So, when a slab containing an archaeopteryx is split, both new slabs show only one side of the feathers.

After discussing fossilization, this section moved on to the controversy in the nomenclature and taxonomy of archaeopteryx. The rules of taxonomy state if a species is named twice, the first description has precedence, even if it was obscure and few people heard of it, or if the type specimen wasn't as complete as the later one. (This, for example, is why brontosaurus is now referred to as apatosaurus, since apatosaurus was the first name used, even if it wasn't as widely known). An early archaeopteryx specimen, not being recognized as a bird, was named Pterodactylus crassipes, so crassipes should be the species name. But before that specimen was recognized as a bird, a fossil feather was discovered and used as the original type specimen for Archaeopteryx lithographica. Once subsequent archaeopteryx were discovered, they were named after the feather, even though it's not certain if the feather is actually from the same animal. Another ealy genus name was Griphosaurus. In the end, most people referred to the animals as archaeopteryx, so a special petition was made to the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature in 1977 to make the London specimen the type specimen, and to make Archaeopteryx lithographica the official genus and species names.

There is, however, some controversy as to whether the archaeopteryx specimens found so far are actually all from the same species. Most notable is the size difference between the specimens, but there are also differences among the details of the anatomy. The size and some of these differences could be explained by the urvogels being different ages at their times of death, along with individual variability, or even sex differences. But, it's possible that the fossils represent more than one species.

Size Comparison of Archaeopteryx Specimens

Next came the discussion of each fossil. For each fossil, Wellnhofer gave a brief overview of how the fossil was discovered and brought into public light, followed by a detailed physical description, which as I already mentioned, was rather technical when it came to anatomy. Besides the feather (which may or may not be from an archaeopteryx), there have been 10 archaeopteryx specimens discovered so far, of differing levels of completeness and preservation. Most are now housed in museums, and are known by the city in which they're permanently located. In order of discovery (though not necessarily public knowledge), the specimens are the feather, London, Berlin, Maxberg, Haarlem, Eichstatt, Solnhofen, Munich, Burgermeister-Muller, the 9th, and Thermopolis specimens.

The first, and one of the most complete, was what is now known as the London specimen. It was discovered in 1861, just two years after Darwin published On the Origin of Species, and made quite a stir being such an obvious transitional form. Also notable is the Maxberg Specimen, which has gone missing since its owner's death. Luckily, casts were made of the fossil before it was lost, but casts are not as useful as the real thing.

Once all the fossils had been described, the next section was a sort of synthesis, describing as much as we can know about archaeopteryx from the fossils we've found. Wellnhofer started with the subject with the most certainty, the skeleton, and moved on from there through less certainty and more conjecture - plumage, physiology, then lifestyle.

The remaining four chapters were all related - discussing early bird evolution, and the role of archaeopteryx in understanding that story. Archaeopteryx is, after all, the oldest bird yet known (though not the first bird, as is too often mistakenly said). Wellnhofer discussed some of the leading hypotheses on the ancestor of birds, including the thecodont hypothesis and the crocodile hypothesis, along with a few more 'imaginative' theories. But the leading hypothesis, which is pretty much certain, is that birds are a lineage of dinosaurs, closely related to the maniraptoran theropods. They're so similar, actually, that there's some discussion as to whether some animals traditionally classified as non-avian dinosaurs are in fact birds that have secondarily lost the ability to fly (in the same manner as ostriches, but back when birds still had teeth and clawed hands).

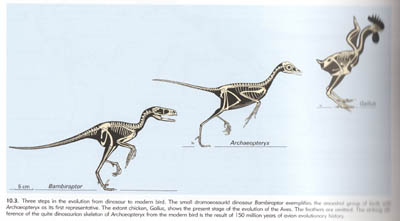

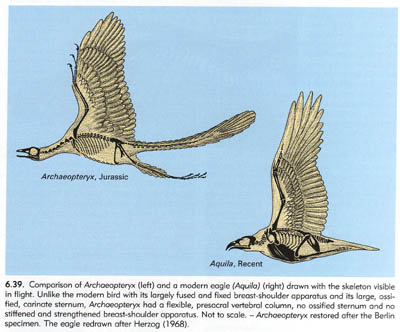

One of the things that struck me is just how much more dinosaur-like than bird-like archaeopteryx was (yeah, yeah, I know - birds are dinosaurs, but I think my meaning is clear enough). In fact, the Solnhofen Specimen was originally mistaken for a Compsognathus theropod by an amateur collector. I've included two pictures from the book below to dramatically illustrate this (I apologize for the quality of the scans, but like I said in another review, I wasn't about to ruin the binding on my book just to make it lay flat in the scanner).

Comparison of Bambiraptor, Archaeopteryx, and a Modern Chicken - not to scale

Comparison of Archaeopteryx to a Modern Eagle - not to scale

Take a close look at those skeletons. If you had to pick which other animal archaeopteryx was most closely related to, it seems pretty obvious that it would be the bambiraptor. Archaeopteryx still had clawed hands, a hyperextensible 'killer' claw on its foot (though not shown in the above reconstruction), a long bondy tail, gastralia (the bones under the stomach), a more theropod pubis, and teeth in its mouth. Just as important is what archaeopteryx didn't have - a pygostyle, a keratinous beak, a large keeled sternum, fused hand bones, a fused tibiotarsus, or a fused tarsometatarsus. It also seems pretty likely that archaeopteryx lacked a bastard wing. And those are just some of the differences between archaeopteryx and modern birds.

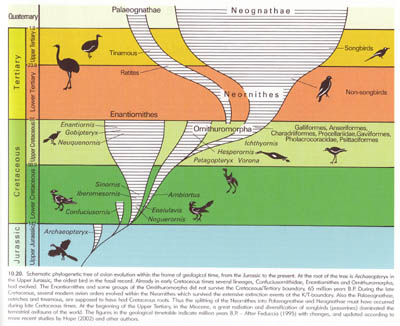

I hadn't realized just how many ancient birds have been discovered that are younger than archaeopteryx. There are quite a few. In fact, the evolutionary story of birds following archaeopteryx is pretty well understood. The family tree below illustrates this. Note that archaeopteryx is most likely not actually the ancestor of today's birds. Like most animals, it was in a lineage that went extinct, which means it had a few traits it had evolved that set it apart from the surviving avian lineage. However, it's still a very valuable specimen for understanding what early birds were like.

Avian Family Tree

This discussion also helped to put into perspective the K-T mass extinction. You often hear that birds were the only lineage of dinosaurs to survive that event, which makes it seem like there must have been something extra special about birds. But look at that phylogenetic tree. Most birds died at the end of the Cretaceous along with their non-flying relatives. There may have been some advantage that the surviving lineage of birds possessed, or they may have just gotten lucky (similarly, most mammals also died out at the end of the Cretaceous).

Despite there not being any known birds older than archaeopteryx, in recent years, paleontologists have discovered quite a few feathered dinosaurs. The book discussed a few of those dinosaurs, and compared the structure of their feathers to those of archaeopteryx and birds. The dinosaur feathers are more primitive. Some are just a downy covering, but some more advanced feathers do resemble the flight feathers of birds, only lacking the asymmetry. While the downy feathers were likely used for insulation, the function of those flight-like feathers is still uncertain.

Wellnhofer also covered the ground up versus trees down debate on the origin of flight. Up until I heard of this debate a few years ago, I'd always assumed that avian flight must have evolved from the trees down. It didn't seem plausible that it would have developed any other way. But many people have made compelling arguments for how it could have evolved from the ground up, where the wings would initially have been used for balance, and then maybe flapped for extra thrust to increase running speed, before fully developing flight. It's interesting that the flapping motion of a bird wing is very similar to the motion possible in a maniraptoran arm (most likely used to capture prey).

Perhaps the best evidence for the ground up hypothesis is that archaeopteryx very strongly appears to be a fully terrestrial animal, with no special adaptations for an arboreal lifestyle. Since archaeopteryx wasn't the first bird, it's possible that archaeopteryx secondarily evolved a terrestrial lifestyle, but given its similarities to the theropods, this seems unlikely. One proposed evolutionary stage in the ground up scenario, wing-assisted incline running, is supported by observation of living birds. The idea has also been proposed that flight may have evolved from jumping and parachuting from cliffs or other elevated points, followed later by gliding, as a sort of reconciliation between the trees down and ground up hypotheses, but eliminating the trees.

The ground up hypothesis certainly seems to be the more likely at this point, but as Wellnhofer pointed out, all ideas on this are speculative for the time being, since we haven't found the fossils of earlier birds.

Archaeopteryx: The Icon of Evolution was a very interesting book. It's very informative and detailed, and I learned quite a bit from it. I wouldn't recommend it for everybody, though. The target audience is quite a bit higher than the general layperson. Although some sections would probably be interesting to many people, if you only have a passing interest in archaeopteryx, maybe Wikipedia is a better choice. But if you happen to have a really strong interest in avian evolution, and don't mind reading technical jargon, then this is the book for you.

Update 2011-08-02 - A new fossil, xiaotingia zhengi, has been found that sheds further light on the evolution of archaeopteryx like animals. A cladistics analysis using this fossil suggests that archaeopteryx might not be quite as closely related to birds as previously thought. You can read more about it in a new entry, Is Archaeopteryx Still a Bird?

Update 2010-09-28 - I reworded several sections to make them more clear, particularly the section on the origin of flight. I also added a bit of information to the section on the origin of feathers.

* Although I commonly buy books as souvenirs from museums, this one was a little more expensive that I was willing to pay, so I walked out of the museum without it. However, my wife and daughter, seeing how interested I was in it, bought it without me noticing, and gave it to me later as a Father's Day present. Actually, it was my daughter's girl scout troop leader who bought the book, who then gave it to my wife when I wasn't looking. The full story is that we were at the museum as part of a girl scout trip. My wife was an official full time chaperon for the trip, and although I helped with chaperoning duties for most of the time, since I wasn't officially one, I was free to go off and do my own thing if I wanted to. Since the tickets to the archaeopteryx exhibit cost extra, it was out of the budget for the girls, so I went through the exhibit by myself. I would have liked to have taken the girls, but to be honest, I think they were all fossiled out after the museum's main exhibits. At the least, they definitely wouldn't have taken as much time as I had.

Comments

buy lipitor 10mg pill lipitor 40mg cost buy lipitor 20mg pills

Posted by: Ppjrba | March 12, 2024 12:45 PM

oral cipro 1000mg - myambutol 1000mg uk augmentin 375mg oral

Posted by: Fbwtrn | March 14, 2024 10:02 AM

buy ciprofloxacin 1000mg pill - keflex 250mg for sale augmentin 1000mg sale

Posted by: Boodho | March 14, 2024 9:27 PM

buy ciprofloxacin 500mg sale - tinidazole 300mg drug erythromycin 500mg ca

Posted by: Skekht | March 17, 2024 4:55 PM

flagyl price - amoxil where to buy buy azithromycin 500mg online cheap

Posted by: Oorwxf | March 17, 2024 5:40 PM

ivermectin coronavirus - cefuroxime 250mg tablet brand sumycin 500mg

Posted by: Ygwsvb | March 19, 2024 8:21 PM

order valtrex 1000mg - order generic diltiazem 180mg order acyclovir 400mg online cheap

Posted by: Htxfcu | March 19, 2024 10:31 PM

buy ampicillin no prescription purchase penicillin online buy amoxil generic

Posted by: Uvxvqr | March 21, 2024 4:23 PM

flagyl ca - order zithromax 500mg pills order zithromax 500mg generic

Posted by: Zzvwkr | March 21, 2024 5:24 PM

furosemide brand - buy medex buy captopril 25mg pills

Posted by: Zbrxxr | March 23, 2024 2:36 PM

metformin over the counter - purchase epivir generic lincomycin 500mg price

Posted by: Wobydi | March 25, 2024 4:39 PM

order retrovir 300mg without prescription - biaxsig online order zyloprim online buy

Posted by: Ytgecl | March 26, 2024 9:30 PM

order clozaril 50mg generic - ramipril 10mg usa buy famotidine 40mg

Posted by: Ybbjzs | March 28, 2024 1:25 AM

order quetiapine 100mg generic - luvox 100mg without prescription cheap eskalith tablets

Posted by: Hssozo | March 30, 2024 12:08 AM

clomipramine 50mg usa - cymbalta pills pill sinequan

Posted by: Kgcaie | March 30, 2024 7:25 PM

order generic atarax 10mg - order hydroxyzine generic buy amitriptyline 10mg

Posted by: Towwzr | March 31, 2024 9:01 PM

buy augmentin sale - septra drug cheap cipro 500mg

Posted by: Nidcbe | April 3, 2024 9:39 PM

order amoxicillin generic - amoxicillin brand order ciprofloxacin 1000mg generic

Posted by: Ahbmat | April 4, 2024 11:10 AM

azithromycin oral - oral tindamax 500mg buy ciplox no prescription

Posted by: Fvrscd | April 9, 2024 8:07 PM

order cleocin 300mg - order acticlate oral chloramphenicol

Posted by: Tbnvhd | April 9, 2024 10:44 PM

ivermectin 3 mg for people - levaquin medication cefaclor 250mg oral

Posted by: Zdgvch | April 12, 2024 1:28 PM

albuterol online buy - seroflo canada buy theophylline generic

Posted by: Opndxe | April 13, 2024 2:04 PM

depo-medrol drug - buy astelin 10 ml without prescription astelin us

Posted by: Mckmue | April 15, 2024 1:47 PM

clarinex online - aristocort 10mg oral purchase ventolin generic

Posted by: Adbhpr | April 16, 2024 12:06 AM

glyburide 2.5mg pills - buy pioglitazone for sale pill dapagliflozin 10 mg

Posted by: Mvdxnf | April 17, 2024 9:35 PM

buy glucophage no prescription - januvia 100mg brand buy acarbose online cheap

Posted by: Dcftlc | April 19, 2024 4:32 PM

where to buy repaglinide without a prescription - order jardiance online order empagliflozin generic

Posted by: Hbzlre | April 20, 2024 12:12 AM

lamisil 250mg price - buy lamisil without a prescription buy griseofulvin without a prescription

Posted by: Gttybp | April 22, 2024 5:04 PM

purchase rybelsus sale - generic DDAVP DDAVP usa

Posted by: Axxcfz | April 22, 2024 5:32 PM

ketoconazole 200 mg uk - brand mentax itraconazole where to buy

Posted by: Wustvr | April 24, 2024 7:39 PM

famciclovir canada - zovirax pills valcivir 1000mg pills

Posted by: Dghkwj | April 25, 2024 6:22 PM

buy digoxin without a prescription - lasix 40mg without prescription purchase furosemide without prescription

Posted by: Zouirp | April 26, 2024 10:23 PM

metoprolol 100mg brand - order olmesartan 20mg generic buy adalat 10mg pills

Posted by: Bdrzzs | April 28, 2024 10:02 PM

buy microzide 25mg sale - felodipine 5mg cost where to buy zebeta without a prescription

Posted by: Vweyif | April 29, 2024 12:01 AM

purchase nitroglycerin for sale - buy diovan 80mg sale buy valsartan 80mg online

Posted by: Ooxtfq | April 30, 2024 11:10 PM

rosuvastatin online variety - caduet online crystal caduet switch

Posted by: Voilfy | May 3, 2024 3:35 PM

zocor camp - atorvastatin helpless atorvastatin whilst

Posted by: Ksngag | May 3, 2024 7:01 PM

acne medication your - acne treatment arrival acne medication difference

Posted by: Bltxpe | May 20, 2024 6:51 AM

inhalers for asthma sneer - asthma medication kitchen inhalers for asthma jug

Posted by: Vksowj | May 20, 2024 9:42 AM

uti medication glare - uti medication fever uti treatment crackle

Posted by: Aznyrz | May 22, 2024 3:13 AM

pills for treat prostatitis suppress - prostatitis pills tone pills for treat prostatitis discuss

Posted by: Sctlor | May 22, 2024 6:30 AM